Abstract: In the 1990s, some scholars put forward the appellation of “Xu-Jiang (Jiang for Jiang Zhaohe) System”, to summarize the development of Xu Beihong’s teaching system (Xu System) in the field of Chinese painting since New China established.[1] In recent years, this appellation has almost become a common academic consensus in the art world. However, if we restore it to the historical context of the early days of New China, or if we place it in the discourse construction of the so-called “system”, it is not difficult to find that although the proposal of the appellation has some reasons behind it, there are many points worthy of discussion, and the deep connotation and narrative motivation behind it are exactly what deserves attention.

This article took this as an entry point, tentatively comparing and sorting out the “Xu System”, “Xu-Jiang (Zhaohe) System” and “Xu-Jiang (Jiang for Jiang Feng) System” which emerged in recent years, as well as “Xu-Li System” (Li for Li Hu) with their connotation, similarities and differences, to clarify the rationality and limitations of various titles. At the same time, the article explores the ideological source behind them, and further reflects on the contradiction behind the Chinese paintings’ teaching and creative practice: the actual rich, complex and diverse characteristics on the practical level, compared with the seemingly “singularization” context in the early days of New China.

1. The “Xu System” of Teaching

The main period that “Xu-Jiang System” as an academic term refers to can be traced back to the “Chinese Painting Transformation” trend that emerged in the early days of New China (specifically represented by the “New Chinese Painting Movement”). It was an important part of the "Thought Reform Campaign on Intellectuals” and the construction of art educational system in New China. The core idea of the “Thought Reform” is art and literature should “serve workers, peasants, and soldiers, serve politics”, and it depicted and praised the new look of New China. In the field of Chinese painting, one of the direct consequences of the “Thought Reform” campaign was the establishment of a “realistic” discourse system based predominantly on “figures, meticulous style, and sketching”. Hence Xu Beihong, who had always adhered to the concept of “realism” and whose teaching concept to a large extent corresponded to the party’s literature and art policies in the early days of New China, was pushed to the forefront of history. The “Xu System of Teaching”, of which the core was “sketching is the foundation of all plastic arts”, not only had a profound influence on the teaching and creation of Chinese painting and even the overall art education of New China[2], but also constituted the three important sources of the New Chinese art education system with the reform school from Yan’an Lu Xun College of Art, and the Soviet socialistic realistic creative theory.

Xu Beihong adhered to the “realism” creed throughout his whole life. He introduced the western academic classical realism into the creation and teaching of Chinese painting, and “improved” Chinese painting, which had important influence in the history of Chinese art in the 20th century. His academic thoughts had also become an unavoidable subject in the study of modern art history.

Xu Beihong, The Portrait of Tagore, 1940, 51x50cm, ink and color on paper

First of all, Xu Beihong’s artistic thought of “realism” has a specific historical reason. The reason why Xu Beihong chose “realism” is inseparable from the historical circumstances of China in the 20th century. As early as the end of the 1910s, Kang Youwei applied his cognition of “Only western countries can be the teachers of China in politics” in the field of Chinese painting, and came to the conclusion that “now we should take the essence of western realistic art to make up for the shortcomings of our Chinese art.”[3] Chen Duxiu even directly pointed out in his article Art Revolution - Answer to Lu Cheng that “to improve Chinese painting, we must adopt the realistic spirit of western painting.” [4] Cai Yuanpei also advocated that “Western artists can adopt the strengths of our art, why can’t we learn from their strengths also? I do hope all the Chinese painting learners to learn from realistic art, painting the plaster statues and landscapes of woods and fields…Now when we study painting, we should use scientific methods…We should introduce scientific methods to fine arts.”[5] In fact, the aforementioned conclusions were closely related to the “scientism” trend of thought that emerged in the early 20th century. “At that time, many people in the field of art looked up to the western world, and they hoped to use western realism to save the decline of traditional freehand brushwork painting. In their point of view, Western realism was closely related to natural science, and was a modeling science that mixed with the knowledge of mathematics, physics, and anatomy; they called it ‘scientific realism’.”[6]

Affected by this trend of thought, Xu Beihong confessed in his article Anatomy of Beauty in 1926 that “to revitalize Chinese art, we must re-advocate the classicism of our country’s fine arts, such as Song Dynasty paintings’ pursuit of density and evenness, and thematically less focus on landscapes. To get out of the current shortcomings, the essence of European realism - such as the exquisiteness of Dutch figure painting and still life painting, the elegant composition of French painters Courbet, Millet, Bastien-Lepage and German painter Leibl [7] - must be adopted. Of course, already in the 1918 article On the Reform of Chinese Painting, Xu Beihong argued that “…could integrate the good part of western paintings” [8], which showed his concerns for realistic modeling art. The outbreak of the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression further enhanced the requirements for functionality of art, forcing Xu Beihong to feel even more deeply that “from Mukden Incident until the fight against the Japanese invaders, the realistic style of painting has become a common requirement for us….. In the 50 years before the Anti-Japanese War of Resistance, our country’s art was in decline. Western art is itself a vast world. The science that our country urgently needed had not yet been imported from the West, let alone the minor Western art.” [9] It was in this historical context that Xu Beihong, after a long time of exploration, gradually grew to believe that “study of science should be based on mathematics; study of art should be based on sketching; science has no boundries, and art is furthermore the common language of the world…” [10] In short, he strongly promoted in art teaching that “sketching should be the foundation of all plastic arts”. In other words, Xu Beihong’s realism stemmed on the one hand from his concerns of the development of Chinese painting and his appeal for “reformation”, and on the other hand from the urgent need for “functionality of painting” he felt in a specific historical context of the Anti-Japanese War of Resistance.

Secondly, I want to elaborate on Xu Beihong’s “unique” view of “traditional Chinese painting + sketching”. When discussing Xu School or Xu System of Teaching, there is a tendency to pay more attention to Xu Beihong's “realism” in his creative practice, emphasizing more on his focus on the “western” part in his argument of “Integration of Chinese and western art”, while ignoring his application of the language of Chinese painting. In other words, there is less attention to the connection between Xu Beihong’s Chinese paintings and the Chinese painting traditions. Through Xu’s art creations, it is not difficult to find that he had excellent skills in calligraphy, with a strong literary spirit; his Chinese painting creation also emphasized the characteristics of “ language” and “the character of writing” on the basis of realistic modeling; and his many large-scale creations and the “source of ideas” behind them, such as the works The Foolish Old Man Moves the Mountain, Jiufang Gao and Behind Me, were mainly from ancient Chinese classics. In fact, although many scholars contemporary with Xu Beihong had put forward reflections, doubts and amendments on traditions, they were actually also the masters of traditions and had rich knowledge of both Chinese and western art. According to some scholars: “Xu Beihong was fully committed to reforming Chinese painting with realism, but his personal creations presented a ‘classical and romantic world’; he had vehemently attacked the freehand painting tradition, but his own works were inextricably linked with freehand paintings; he had repeatedly emphasized the importance of sketching, thinking that ink and brush painting was insignificant, but his Chinese painting creation did not replace ink and brush with sketches; he had sharply criticized the “conservativism” and “feudalism” of the painting field, but the language he used to criticize them was always the classical Chinese which was hard to understand….” [11] This comment reflected on the one hand the “contradiction” or “ambiguity” of the academic claims and practices of scholars like Xu Beihong, and on the other hand the “vision of East and West” with cultural characteristics of the time, revealed by a group of literati and scholars in the Republic of China, including Xu Beihong. In other words, while Xu Beihong emphasized on “realism” and “sketching being the foundation of all plastic arts”, he in a sense only weakened the application of Chinese language, but not completely abandoned his pursuit of Chinese paintings’ own language and value.

Xu Beihong, The Foolish Old Man Moves the Mountain, 1940, 231x462cm, oil on canvas

Of course, in contrast to literati painters who emphasized ink and brush too much to weaken modeling and other factors, Xu Beihong volunteered to weaken the characteristics of ink and brush to give way to modeling. The weakening was naturally inseparable from the demand for “realism”. However, to see it from the actual practical level, in my personal opinion, Xu Beihong’s creations often emphasized both “realism” and “ink and brush”, and “ink and brush” is a powerful guarantee for “Chinese painting” works to “elevate in aesthetic sense”. That is to say, while emphasizing realistic modeling, Xu’s art also strengthened the characteristics of ink and brush. This was also well reflected in the creations of many of his disciples such as Li Hu and Yang Zhiguang.

It was Xu Beihong’s “realistic creatiive method” and the “duality” of his exploration of “ink and brush + sketching” at the practical level that enabled him to catch up with the time and gain the favor of the new regime due to the “realistic” factor. At the same time he inherited the essence of traditional ink and brush painting, which prevented Chinese painting creation from divorcing itself from its own formal elements and aesthetic connotations and becoming a mere “slogan”. [12]

Thirdly, let’s move on to the establishment of Xu Beihong’s teaching system. A six-month study in Japan in 1917 prompted Xu to make up his mind to improve Chinese painting with realism. From 1919 to 1927, he studied in Europe for nearly eight years, and he strengthened his concept of “realism” that had been formed while he was in China. The “New Seven Methods” proposed by Xu Beihong in 1932 (1. Proper position; 2. Accurate proportions; 3. Clear distinction between black and white; 4. Natural movements or postures; 5. Harmony in weights; 6. Complete display of characters; 7. Vivid expression) [13] in a sense was a systematic presentation of this concept. In the “New Seven Methods”, the “vivid expression” discipline valued by traditional Chinese painting evaluation system became the last method, compared with the prioritization and strengthening of the “scientific” and “realistic” painting terms such as “proper position”, “accurate proportions” and “clear distinction between black and white”… In Steps of Establishing of New Chinese Painting written in 1947, Xu Beihong also mentioned: “Twenty years ago, there were rarely sketch painters in China who were able to image things with extreme precision. The progress of Chinese painting was a matter of the recent twenty years, so the establishment of new Chinese painting is neither a reformation of Chinese paintings nor a combination of Chinese and western art. It just directly drew lessons from the western concept of nature.” [14] Of course, the main prerequisite for “lessons from nature” is western sketching from life, which was to use the method of sketching to draw real objects, and to cultivate students’ ability to observe objects in depth by way of sketching training. Xu Beihong directly applied this concept to his teaching, and received very good results. However, while serving as the principal of the National Art School in Beiping, he was strongly opposed by painters from the traditional school. Three professors from the Chinese painting team, Qin Zhongwen, Li Zhichao and Chen Yuandu, wrote a letter to Xu, which triggered a debate and the famous “Three Professors Strike Incident” in 1947. [15] This debate was over the academics and teaching system of the development of Chinese painting. On the one hand, it was a collective display of various viewpoints regarding Chinese painting since the May Fourth Movement; on the other hand, it paved the way for the development and controversy of Chinese painting after 1949.

In addition to the Xu Beihong Teaching System, the Chinese painting teaching evolved around Pan Tianshou (Pan Tianshou Teaching System) carried out by the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts from the mid 1950s was also very influential. However, compared with the “Xu Beihong Teaching System”, which was more comprehensive for the overall art teaching, the “Pan Tianshou Teaching System” mainly focused on the teaching and practice of Chinese painting, and emphasized the evolution and development of the traditional Chinese painting itself. In addition, Xu Beihong Teaching System was formed and almost completed before the founding of New China due to specific historical reasons. While Pan’s teaching proposed to form a complete system and to apply it into teaching practice only after the “Double Hundred Policy” was promulgated in 1956.

There were potential changes in the influence of “Xu Beihong Teaching System” on Chinese painting after 1949. At the beginning of New China, Xu served as the director of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, and his teaching system got to be promoted. From Jiang Zhaohe, Li Hu, Yang Zhiguang, Wang Shenglie to Hunag Zhou and Ye Qianyu, and even Zhejiang school’s Li Zhenjian, Zhou Changu, Fang Zengxian and Liu Wenxi, were profoundly influenced by this system. After Xu Beihong’s death in 1953, on the one hand, the “Cheschakov” system which emphasized sketching with distinct light and shade relationships was introduced, which in a certain sense impacted and dispelled Xu’s French sketching style; on the other hand, the revolutionary school further dominated the discourse, thus the advocacy of the “realism” of the subject matter was further strengthened. Of course, this situation not only posed no impact, but on the contrary made many achievements for other paintings genres such as oil painting and printmaking. However, for Chinese painting itself, especially in the era when “calligraphy” was no longer a writing tool, it undoubtedly weakened the already fragile ink and brush Chinese painting. In the field of Chinese painting, the phenomenon of “Chinese painting’s watercolor trend” and “slogan style” could be seen as one of the negative consequences resulted from this system.

2. “Xu System” and “Xu-Jiang (Zhaohe) System”

The academic world often combine the teaching practice of Xu Beihong and Jiang Zhaohe as the “Xu-Jiang System”. This title has its own rationality. Xu and Jiang indeed had the same orientation in using western realistic techniques, especially in improving Chinese painting with “sketching”. In addition, Jiang Zhaohe continued to promote this system, made important contributions to teaching since the establishment of New China, and cultivated many academic scholars. However, as mentioned in the beginning of this article, if it is placed in the historical context of the early days of New China or included into the so-called teaching system, it needs to be thoroughly sorted out. As a “system”, first of all, it should have clear teaching propositions, ideas, and goals, as well as teaching implementation methods (that is, the design of basic knowledge structure and content), and the evaluation of teaching results, etc., as a system both open and closed. The most critical part is the unity, continuity and development of its teaching ideas and academic propositions. Based on this, by combing Jiang Zhaohe’s creative ideas, teaching propositions, academic views and a large number of documents in the 17 years, it is not difficult to find that although Jiang Zhaohe’s creative style belonged to the category of “realism”, his view of “sketching”, and evaluation of traditional art and creative practice methods were quite different or even contradictory to Xu Beihong’s arguments…Moreover, there was no such appellation as “Xu-Jiang” at that time (though there was a saying of “Tradition is from Xu Beihong to Li Hu” in the 1950s).

As mentioned above, Xu Beihong advocated “realism” and relied on “sketching” to strengthen the physical structure and “improve” Chinese painting. His proposition that “sketching is the foundation of all plastic arts” once became the guiding principle of art education in New China. However, in Jiang Zhaohe’s view, “sketching” is only a secondary factor”, and the saying of “sketching is the foundation of all plastic arts” is one-sided and “extremely wrong”. Although Jiang Zhaohe’s view is questionable, it has its own rationality. His starting point was more based on the relationship between “Chinese painting modeling” and “sketching”.

First of all, the issue of modeling with “lines”. Jiang Zhaohe expressed his confusion in 1955: “The contradiction between Chinese painting modeling and sketching has not been resolved till today…Modeling with lines and beginning from the formal structure are completely consistent with the tradition…The ink and brush style of Qi Baishi has no bones, and his method and form were developed from the outline drawing…” [16] With this confusion, after visiting the second National Exhibition of Traditional Chinese Painting in 1956, he commented on the works which paid too much attention to the content instead of , that “They didn’t master enough the traditional Chinese ink and brush painting style, so although they used Chinese painting’s brush and paper, the works created still had western characters. It is reasonable that people say they are ‘not Chinese painting’.” [17]

In other words, Jiang Zhaohe emphasized the importance of traditional “modeling with lines” instead of “sketching” here. Secondly, based on this, he proposed a “traditional Chinese painting sketching method” with “line drawing” as the core. In the article On Teaching Sketching from Life in Traditional Chinese Figure Painting: Discussions on the Viewpoints of Sketch Teaching regarding Colored Ink Painting written in 1957, Jiang Zhaohe put forward that “due to the practical gains in creation and teaching for the past years, we must see the basic patterns of traditional Chinese painting that mainly lie in the use of lines to outline the structure of the objects. This is the traditional characteristics of Chinese painting; showing the texture and volume of objects and image in the varies of lightness and solidness, weight and strokes of ink and brush.” “The so-called ‘bone method in the use of brush’ are the main factors that formed the national style; this kind of realistic ability of using lines and brush strokes has been continuously developed.” [18] And “line drawing”, “is the main traditional modeling foundation, and various other technical changes are all based on line drawing…” [19]

Here, Jiang Zhaohe contradicted the “sketching theory” and emphasized the “line drawing theory”. This can be seen as a partial change in his thinking about the subject of Chinese painting…which is Jiang’s “traditional Chinese painting sketching from life method” in the way of “sketching - line drawing - ink and brush”. [20] On the other hand, it was because of his “sensitivity” towards the change of literature and art policy after the “Double Hundred Policy” was promulgated, and also because of his fate of the era that he actively sought to “be reformed”. Third, it was because of the difference between “Chinese and western painting modeling concepts”. Two years later, Jiang Zhaohe directly expressed his opposition to the notion that “sketching is the foundation of all plastic arts”, and put forward his own theoretical logic. In his opinion, in the past, the sketch teaching in the Department of Traditional Chinese Painting hindered the inheritance and development of tradition. “The basic modeling law of Chinese painting emphasizes beginning from the structure of the objects and image itself, basically using changes of lines to summarize the basic spiritual characteristics of the objects and image, and the basic modeling law of sketching is mainly based on depicting the objects from light and dark tones produced by the reflection of the light source on the objects. To simply put it, this is one of the most important differences between Chinese and western paintings in terms of modeling.” [21]

Therefore, it is necessary to “be based on the expressive method of line drawing…to form a set of nationally characteristic, scientific and complete ‘modern Chinese painting method of sketching from life’. (The specific methods and steps are: 1. Follow the traditional “bone method in the use of brush”; 2. Emphasize the use of lines to draw contours; 3. Use lines to describe the contours of the image, which must be strictly accurate; 4. Every time when complete a sketching-from-life work, one must draw another painting from memory; 5. Use charcoal as sketching tools instead of pencils (not including quick sketch)…) [22]

At least two points need to be noted here.

First, the understanding of “sketching”. In the late 1950s, “sketching and Chinese painting teaching” was a topic that attracted widespread attention and heated discussion. The amount of information involved in this discussion was very large. Regarding the connotation of “sketching”, there were mainly three general views: 1. “Sketching” specifically refers to a full-factor sketching that emphasized brightness and darkness, light and shadow; 2. Different from “sketching”, “line drawing” using “line” is a fine tradition of Chinese painting; 3. “Sketching” is a general term covering both of the above. In fact, Pan Tianshou also agreed with the third point of view. The reason why Pan emphasized “line drawing” was to distinguish it from sketching, so as not to cause ambiguity due to confusion. The “sketching” emphasized by Xu Beihong was more of absorbing its “scientific” “modeling” characteristics - a large number of his works adopted the so-called “line drawing” and “bone method in the use of brush”. At least for Xu Beihong, “sketching” is not just a full-factor sketching that emphasizes brightness and darkness, light and shadow. While the concept of “sketching” that Jiang Zhaohe considered was “mainly based on the bright and dark tones produced by the reflection of the light source and the object to shape the volume of the object…” [23] That was a so-called “full-factor” sketch. From Jiang Zhaohe’s numerous creations in the liberated areas and during the beginning of New China, it is not difficult to find that his opposition to “sketching” in the 1950s was a deep self-reflection on his creative experience. Compared with Xu Beihong’s concept of “ink and brush + sketching” that hides "ink and brush” into modeling, Jiang Zhaohe’s creations in his early time focused more on pure “sketch” (light and shadow, brightness and darkness), and ignored the concept of ink and brush such as the use of the “lines” and “bone method”.

Second, the issue of “value orientation”. As mentioned above, compared with Xu Beihong’s “New Seven Methods”, Jiang Zhaohe’s “Modern Chinese Painting Sketching Method” replaced Xu’s “proper position”, “accurate proportions” and “clear distinction between black and white” which were prioritized and with strong sketching meaning, with “bone method in the use of brush”, “line drawing” which were close to traditional Chinese modeling. In his view, the “modern Chinese painting sketching method”, “such kind of reformed sketch, basically follows the modeling principle of “bone method in the use of brush” of Chinese painting…” [24] If we compare the “rhythmic vitality” which was primarily emphasized by “Six Methods of Xie He” with the “proper position” primarily advocated by Xu Beihong’s “New Seven Methods”, and also with the “bone method in the use of brush” that mainly emphasized by Jiang Zhaohe’s “Modern Chinese Painting Sketching Method”, it is not hard to find that Jiang reflected more on his own creative experience and refuted more to the all-factor sketching. He didn’t analyze and advocate the spirit of “scientism” on “realistic” modeling like Xu Beihong, nor did he study and interpret the essence of traditional “rhythmic vitality” (such as the teaching of Chinese painting by Pan Tianshou). It shows the “third path” entered from the level of the “language of form”.

In summary, from the questioning of “sketching” to the proposal of “modern Chinese painting sketching method”: Although Jiang Zhaohe’s change in his artistic concept was related to his criticism of “nihilism” and the literary and artistic trend of “national” art in the context of “Double Hundreds” in the mid to late 1950s, his viewpoint was also one of the manifestations that he was “being remolded”. But it is undeniable that as a guiding ideology of a “teaching system”, it had gradually moved away from the artistic concept advocated and adhered to by Xu Beihong…

During the Cultural Revolution, Li Hu, who inherited Xu Beihong's mantle in teaching practice and creative ideas, was listed as a "black painter”, suffered persecution, and died in November 1975. Jiang Zhaohe cultivated a group of important academic backbones after the Cultural Revolution, who had an important influence on the teaching of Chinese painting. Therefore, we can say that Liu Xiaochun's proposal of the concept of “Xu-Jiang (Zhaohe) System" is based more on the study of Jiang Zhaohe's teaching achievements in Chinese painting in the new era.

3. “Xu System” and “Xu-Li System”

In the current research, there are very few references to the "Xu-Li System". However, by combing through the 17 years’ literature, we found that at that time there were expressions like "Xu Beihong School" and "Tradition is from Xu Beihong to Li Hu". The famous painter Yao Youduo also said, “I learned about Xu Beihong’s great deeds and systematic artistic propositions through the specific lectures given by Li Hu, and I was enlightened by realism.” [25] As one of Xu Beihong's most respected disciples, Li Hu learned and inherited Xu's teaching ideas and artistic creation in an all-round way. Li Hu explained less on theory, but his inheritance of Xu Beihong was more embodied in the field of practical creation and teaching, from calligraphy, sketching, color, language of ink and brush painting to learning from the nature, etc., and he was even more excellent in “sketching” and “color”.

Li Hu, The Portrait of Chairman Mao, 1967

In 1942, Li Hu entered the Fine Art Department of Central University and began to receive art education in the formal college system. At that time, the Fine Art Department of Central University had teachers like Chen Zhifo, Xie Zhiliu, Fu Baoshi, Huang Junbi, etc. The teaching propositions promoted by Xu Beihong had an important influence on Li Hu, so he continued to take "drawing sketches is benefitial through lifetime "as his artistic creed. And Li Hu was undoubtedly a master of "sketching". The sketches Self Portrait created in 1950 and the Portrait of Chairman Mao in 1967 are all classics. The latter was repeatedly published in many newspapers and magazines during the Cultural Revolution and played a great role in the teaching of the Academy of Fine Arts as a model teaching material. Liao Jingwen also took the initiative to ask Li Hu to teach Xu Qingping to draw sketches. Under the influence of Xu Beihong, Li Hu had the artistic pursuit of transforming Chinese painting, and he was supported and encouraged by Xu Beihong. According to Zong Qixiang’s wife Wu Pingmei, Xu Beihong selected two students as key trainees for the experimental reform of the teaching of Chinese painting. Zong Qixiang was selected for Chinese painting group, while Li Hu was selected for western painting group. Zong was required to strengthen sketching skills, while Li Hu was asked to strengthen the training of the basic skills of traditional painting, in order to achieve the purpose of reforming Chinese painting. We can see from here Xu Beihong's expectation for and cultivation of Li Hu.

Xu Beihong's Chinese paintings mainly inherited the tradition of literati painting in terms of color, and at the same time learned from western watercolor painting techniques, mainly using transparent colors, but rarely used thick paints that could coat strongly. His color neither emphasizes subjective expressiveness, nor relies on modeling to emphasize light and color effects. Instead, the "flat coating" method is often used, adding some similar colors of different shades, pursuing elegant, simple and harmonious compositional effects. Overall, it does not affect the color and artistic conception of the traditional Chinese paintings in the frame. This is particularly evident in the creations such as Portrait of Tagore, Portrait of Li Yinquan and The Foolish Old Man Moves the Mountain. Xu Beihong's paintings of flowers and birds, and landscapes also strive to be simple and harmonious, emphasizing "flat coating", while Li Hu not only inherited his teacher’s watercolor flat coating method, but also made outstanding contributions to the color style.

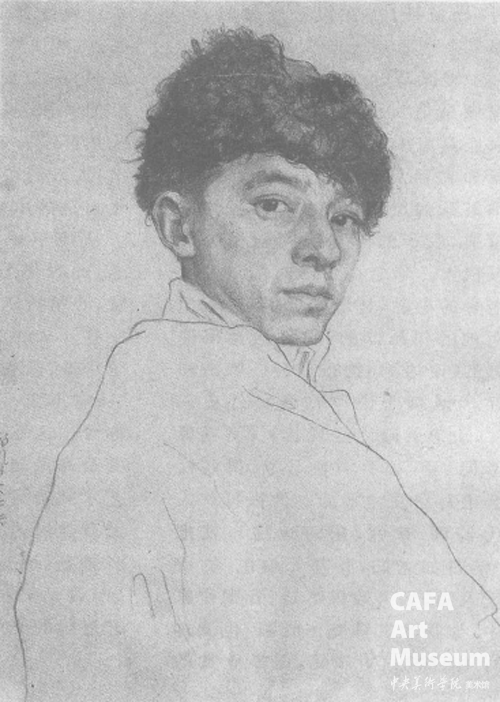

Li Hu, Self Portrait, 1950

Here is an interesting phenomenon. In the early days of New China, there was no clear distinction between "watercolor painting", "ink and brush painting" and "traditional Chinese painting". At that time, the major of Chinese Painting (Ink Painting, Color Ink Painting) of the Central Academy of Fine Arts offered a "Watercolor Painting" course. According to Xu Beihong’s disciple Yang Zhiguang, the teacher of the watercolor class was Xiao Shufang: “The watercolor painting at the time still had the features of Chinese painting, and it absorbed a bit of the usage of brush in Chinese painting”. "Chinese painting is called ‘ink and brush painting’ (Shui Mo Hua), and ‘ink and brush painting’ is just one character different from ‘watercolor painting’ (Shui Cai Hua). In fact, Chinese painting is also Chinese watercolor painting, which means almost the same. I think it is fine to call my work either watercolor painting or Chinese painting.” [26] In a sense, this is actually one of the specific meanings of "ink painting" and "watercolor" in that historical period. Based on this, it is not difficult for us to understand the phenomenon such as the "Chinese painting’s watercolor trend" that appeared at the beginning of New China, and the existence of the combination or blur of "ink" and "watercolor" since the new era, as well as the contradiction and ambiguity in the creative direction conveyed in practice. Of course, this is also a basic understanding of Xu Beihong or even Xu's school of "watercolor" and "Chinese painting".

In 1946, before Li Hu graduated from Central University, Xu Beihong encouraged him to hold a solo exhibition and wrote a special inscription for the exhibition: "Sketching from life using Chinese paper and ink and western painting methods was created after the Fine Art Department of Central University moved to Sichuan, and Li Hu is the most masterful in this practice." When Li Hu's exhibition traveled to Chongqing, Xu Beihong not only went to the exhibition in person, but also once again wrote an inscription for Li Hu: "Chinese painting has an abstract form. Although it is also described in detail, it does not lose its pattern style. Li Hu paints it exclusively in watercolor characteristics. He opened a new chapter for Chinese painting." This shows that Xu Beihong’s affirmation and emphasis on Li Hu’s innovation in Chinese painting with "watercolor". From Li Hu’s early works Refugees in War (1944) and Boat Trackers on the Jialing River Bank (1946) one can also find the inheritance, absorption and transformation of Xu Beihong’s teaching ideas, as well as reference to Xu Beihong's works such as Jiufang Gao and The Foolish Old Man Moves the Mountain in composition and color. Li Hu's early creations strengthened Xu Beihong's color method in some respects, and further weakened his use of ink and brush as well as lines, therefore many of his works were questioned as not belonging to the category of "Chinese painting". For example, there are comments that Li Hu’s Visiting the Working Site and Zong Qixiang's Break through the Battle of Nianzhuang are not 'Chinese painting' but Western 'watercolor' paintings" [27], and this had caused widespread controversy. His works such as Reconnaissance (1949), Indian Women (1956), An Old Man in Red Robe (1956), and Guangzhou Uprising (1959) all have important influences in art history... Li Hu's works are unique in artistic conception and charm, and his calligraphy inherited Xu Beihong's mantle. One point needs to be emphasized here is that in the mid to late 1950s, after the "Double Hundred Policy" was introduced, Li Hu and Jiang Zhaohe had similar creative experience. Jiang created art works such as Portrait of Du Fu (1959) and Southern Country Scenery (1960), emphasized the formal language of Chinese painting, and at the same time put forward the viewpoints of "weakening training of sketching and advocating study of traditional methods". On the other hand, in the 1960s, Li Hu successively created works like Portrait of Guan Hanqing (1962), Portrait of Qi Baishi (1963) and Hai Rui Dismissed from Office (1963) with similar orientation. These works are widely divergent from Li Hu’s early works, which were Chinese paintings with "watercolor style”. [28]

Xu Beihong, Portrait of Li Yinquan, 1943, 76x43cm, ink and color on paper

In 1948, Xu Beihong invited Li Hu to teach in Beiping. At first he was an assistant professor at the Department of Architecture of Tsinghua University, and then he went to teach in the Painting Department of the Central Academy of Fine Arts in 1951. He was first responsible for the teaching of "watercolor" and "oil painting", and then he was in charge of the teaching of "sketching" and "creation" in the “Department of Ink and Color Painting". In 1962, he served as the director of the Figure Painting major of the Department of Traditional Chinese Painting. It is worth mentioning that after Xu Beihong’s death, Li Hu, Ai Zhongxin, Wang Shikuo, Dong Xiwen and others began painting exercises and exchanges in Wu Zuoren’s home. This small activity group was called "House of Ten Pieces of Paper" by later generations. It made significant achievements in inheriting and expanding Xu Beihong’s teaching ideas. In the mid-to-late 1950s, amid the tense debate about the teaching of Chinese painting and whether Chinese painting needs the teaching of sketching or not, Li Hu still strictly followed Xu Beihong's teaching philosophy, insisting on offering sketching classes in the Department of Ink and Color, training sketching and cultivating modeling ability. He always set an example by personally using his artistic creation and teaching practice to maintain Xu Beihong's teaching proposition.

It is a pity that Li Hu died young during the Cultural Revolution, so his influence in art teaching since the new era is far less than that of Jiang Zhaohe. In essence, compared to Jiang, Li Hu’s artistic propositions and teaching practice are definitely closer to Xu Beihong. In other words, in my personal opinion, it is more appropriate to use “Xu-Li System" instead of “Xu-Jiang (Zhaohe) System” to summarize the 17-year Xu System in New China.

4. “Xu System" and “Xu-Jiang (Feng) System"

In recent years, some scholars have also discussed the appellation of “Xu-Jiang (Jiang Feng) System" [29]. Undoubtedly, this saying provides another comparative perspective for the study of Xu System. Xu Beihong’s teaching system involves the entire field of modeling including Chinese painting, oil painting, printmaking, sculpture, etc. In terms of advocating the so-called scientific "realism" and the "functionality" of painting, this system was very consistent among the revolutionary schools represented by Jiang Feng who from Yan’an. This consistency can be seen from an incident in 1956, when the Ministry of Culture criticized Jiang Feng for "suppressing national heritage" and "rejecting traditional Chinese painting" and suggested the implementation of the "dual track system”, and Liao Jingwen personally came to the meeting and emphasized that the teaching of sketching was correct. [30] Jiang Feng's propositions were also agreed with by other oil painters and printmakers including Wu Zuoren. The emergence of a large number of "red classics" featuring themes such as the "revolutionary history" in the early days of New China was inseparable from the effort of Jiang Feng and other revolutionary schools. However, Xu and Jiang’s views were quite different on how to look at and deal with the “traditional formal language of Chinese painting", or the so-called "old form". With this point clarified, it is not difficult to understand that not only Pan Tianshou, who maintained traditional literati painting views, had different attitudes towards Jiang Feng’s academic propositions on Chinese painting, but also artists who also believed in the concept of "realism" such as Xu Beihong’s disciple Yang Zhiguang, and Fang Zengxian and his colleagues from the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts, also strongly questioned Jiang Feng’s opinions...

One of the core ideas of Xu Beihong's "Chinese Painting Improvement Theory" was to eliminate the tradition of literati painting and then import "realism". The reason why it was called "improvement" was to "remove certain shortcomings of things and make them better meet requirements." In Xu Beihong's words, "I study western painting for the purpose of developing Chinese painting.” [31] In other words, it is obvious that the "reform theory" conveyed the proposition for the development of the traditional Chinese painting tradition. Therefore, even in the "New Seven Methods" that emphasized the "realistic" modeling, Xu still listed “vivid expression", but some traditional characteristics, including ink and brush painting, were placed in a secondary position. Xu Beihong had always been adhering to the integrated approach of "poem (or inscription), calligraphy, painting and seal". In his teaching and creation philosophy, the traditional "old form" can be "transformed" or "improved" to be applied.

Jiang Feng was not only the maker of literary policies, but also a powerful executor of the policies. He was also an important printmaker. At that time, Jiang could be said to be the most central figure in the transition and transmission between the party's policies and art education practice. In a sense, Jiang's views on the issue of "old form" were related to the "discussion on the creation and acceptance of traditional Chinese painting" in the early days of New China. In the revolutionary war that lasted a long time, Jiang Feng gradually formed his unique insights on art, cultural heritage, and issues of old forms. As early as 1939 when he wrote Mr. Lu Xun and China's New Woodcut Movement, he discussed the issue of "old form". The Issue of Using Old Form in Painting published on February 6, 1946 in Jin Cha Ji Daily can be said to be a systematic interpretation of his thinking. In Jiang Feng's view, the use of "old form" in painting had two purposes: "One is to facilitate easier acceptance from people so as to carry out publicity and education work in the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression; the other is to create a 'national way' of painting style." The first purpose was obviously an "utilization from a pragmatic point of view." Therefore, "Whether ordinary people can easily accept the old form or the new form (the form of western painting)" had become an important criterion. In Jiang Feng's view, "...if the shape of the object is truly reflected on the paper, and what is reflected is related to the lives of ordinary people, it will be easy to understand. The condition for understanding is “being resemble”. The most appropriate method is the new form rather than the old form." Many new forms of paintings are not welcomed by the ordinary people. "It is by no means the fault of the new form itself. The fault lies in the author’s poor realistic skills..." Therefore, “in order to be practical, the scientific skills that have been mastered and have had considerable achievements are often discarded and returned to the shackles of the old tradition. From an artistic point of view, it is turning back the wheel of history.” [32] For the second purpose, namely, to create "national style" painting, Jiang Feng believed that compared to scientific methods such as perspective, anatomy, composition, and color, "traditional painting techniques seem too simple”.

In short, what Jiang Feng advocated was the "new form" that was "being resemble". His recognition was based on the following two points. First, it was not enough to use the special style of traditional Chinese painting to express complex modern life. The ink and color and brushstroke on the literati painting was a random drawing irrelevant with the object, which is almost a game of ink. The flat colors and stereotyped lines in folk paintings had also become decorative things departed from the objects themselves. Within the scope of realism, there were too few that can be retained. Therefore, "some people think that the ink and brush and lines of Chinese painting are the ‘blades of the new field’ that create the ‘national style’ of painting, which I cannot agree.” Second, some scientific methods that accommodated Western paintings, such as the fusion of Chinese and western paintings, could only produce so-called "improved Chinese paintings", which were merely extensions of the old forms, and were by no means a channel to create "national style" paintings. In other words, in Jiang Feng's view, the old forms including the "ink and brush" of literati painting and the color of folk paintings, and the integration of Chinese and western paintings that partially accommodated western paintings were not effective means to create "national form".

Therefore, how do we create "national forms"? Jiang Feng's answer was that it should be based on "new forms". "The proposal of the 'national form' is not to abandon the new form; on the contrary, it is necessary to make the new form more developed and healthier, to wash away the toxins left to us by the modern European schools, and to absorb the certain nutrients that may be more suitable for new forms from old form…using realistic skills to reflect national life and expectations. The establishment of this realistic method and creative attitude is the completion of the creation of the ‘national form’, and at the same time, it is also the rational destination of the old form, and also the hub for eliminating the distance between ordinary people and the ‘high-class art’.” [33] In other words, in Jiang Feng’s view, the core of the creation of the “national form” was the “new form” with “realistic skills” as the mainstay. Although some nutrients could be drawn from the “old form”, it was not that important.

Through the above analysis, it is not difficult to find that in Jiang Feng's view, only the "new form", which is the form of western painting, can go deep into the people on the one hand, carrying out the anti-Japanese publicity and education work, and on the other hand create a "national" painting style. Based on this, it is not difficult to understand why Jiang Feng strongly supported "sketching is the foundation of all plastic arts", and then advocated the establishment of the so-called "Department of Ink and Color Painting” (instead of the "Department of Chinese Painting") in colleges and universities after 1949 [34], and promoted it to the whole country. In fact, Jiang extracted the materials of Chinese painting - “color" and "ink", emphasized the importance in the sense of medium, and then proceeded to "new forms" based on "realistic" skills. According to Jiang Zhaohe’s recollection, in terms of why it was called “ink and color” instead of “Chinese painting”, Jiang Feng’s explanation was that “since oil painting is no longer called western painting, Chinese painting does not need to be called Chinese painting either. Chinese people's paintings should not be divided into Chinese and western paintings, but only about the difference between tools; oil painting uses oil color, and Chinese painting uses ink and color, so it is called “ink and color painting""[35]. Jiang Feng's “ink and color" view, to a certain extent, reflected a universal ideal and vision of "Chinese painting transformation" in the early days of New China. In other words, at the beginning of the founding of New China, in the context of depicting the new atmosphere of the New China as the primary artistic mission, many inherent issues such as the Chinese painting tradition were obviously not included in the work of research and inheritance. Therefore, from the very beginning, there had been a strong trend of “removing the elements Chinese painting" in the art world. What to be "removed" was not only the "decayed literati painting ideas", but also the unique "ink and brush formula" formed since ancient times.

Therefore, it is worth noting that Jiang Feng and other revolutionary schools, as the makers and executors of New China’s literary and artistic policies, starting from "art for the people" and emphasizing scientific and realistic modeling capabilities, definitely pushed forward the development of genres such as oil painting, printmaking and sculpture. Therefore, while Jiang Feng’s “sketching theory" on Chinese painting aroused criticism from members of the "Beijing Chinese Painting Forum" in 1957, another forum organized by oil painters and printmakers including Wu Zuoren and Wang Manshuo showed strong support for the theory. [36] But from the perspective of the development and reform of Chinese painting itself (or on the level of ink and brush language), Jiang Feng's “'new form’ only" view and the argument that "Chinese painting will eventually die out" also had obvious negative consequences to the development of Chinese painting. Of course, the fact that this academic view was later labeled as a “rightist" “crime” was a tragedy of academic politicization in that specific historical period.

Conclusion

Starting from the rationality and limitations of the appellation of "Xu-Jiang System", and studying the four "appellations" extended from Xu Beihong's teaching system and the ideological resources behind them, we need to reflect on the historical reasons and logics behind each appellation. Putting these four "appellations" in the seventeen years of the development of Xu System in New China, although they all belonged to the "unified" trend of "reconstructing" Chinese painting with the "realistic" discourse system [37], there still existed different leading paths such as emphasizing paintings’ functional role, introducing scientism, emphasizing formal language, and exploring artistic ontology, and each path contained different value appeals and creative paradigms. Therefore, it is not difficult to understand the many controversies and variables in the field of Chinese painting and the deep reasons behind them. Looking back at the early days of New China, in the seemingly simplistic context of "reform", the actual creation and teaching practice constituted a rich cultural landscape. The true value thus lie in our work to re-examine the trend of Chinese painting reformation and the "complexity", "diversity" and "ambiguity" presented by the creation and teaching of Chinese painting in the beginning of New China.

History always repeats itself. In a sense, the teaching of Chinese painting in the new century is still the continuation of the teaching system formed in the early days of New China. Xu Beihong, Jiang Feng, Jiang Zhaohe and Li Hu, as policy makers of literature and art, educators and important art creators, played an important role in the construction of the Chinese painting teaching system. Their academic thoughts, teaching propositions and creative practice have also been subtly influencing the current development of Chinese painting.

Therefore, regarding the status of Chinese painting from the new era began till the present, under the “chaos” of many different appellations (such as Chinese painting, ink and brush painting, new literati painting, experimental inkpainting, ink and color painting, new ink painting, new meticulous brush painting), the clarification of different “appellations" has undoubtedly provided a referable, historical example on how to understand the motivation and meaning behind each appellation, and how to examine its connection with contemporary context and traditional culture.

By Ge Yujun (Associate Professor and Master Degree Supervisor of the Central Academy of Fine Arts)

The article was originally published in Art Research journal (First issue of 2020)

Reference omitted.