By Ann Demeester

"There is an abc-ignorance that precedes knowledge, and there is another learned ignorance that comes after and that is created through 'knowing' and that will equally like the first be annihilated and annulled by knowledge.'

Michel de Montaigne[1]

Do not assume that this text will proceed smoothly from alpha to omega; it will progress haltingly, ideas will be stumbling, concepts bungling, judgments stumbling and tripping.

Tripping seems one of the most adequate metaphors for describing a learning process. Without taking heed or notice you run into an unexpected obstacle, almost fall over, but recover yourself just in time. Collapse, pain, or catastrophe were imminent but did not materialize. Adrenaline rushes through your veins, thinking momentarily comes to a halt and all you do or can do is act instantly without reflecting or even briefly considering the matter. You narrowly avoided a misstep; consequently your awareness of potential hindrances is heightened and you devise methods and ways of surmounting similar hurdles, avoiding obstructions that impede future achievement or progress. You try to understand how you can dodge encumbrances, skip over impediments with light and quick steps. Tripping is an-almost-mistake, a-not-yet-blunder. It does not imply failure but it brings you to the verge of falling/failing. It makes the contact or close encounter with a dangerous crash or a disturbing debacle palpable and creates a feeling of urgency and "total attention." You were almost overpowered, almost disarmed and were on the verge of being extremely vulnerable, but you succeeded in “de-turning” or undoing that alarming situation. After “tripping" you are sightly fearful of making yet another mistake but you are intensely concentrated and prepared, fully, for whatever comes next.

In one of her most inspiring texts, theoretician Irit Rogoff states, ‘Criticality’ as I perceive it is precisely in the operations of recognising the limitations of one's thought for one does not learn something new until one unlearns something old, otherwise one is simply adding information rather than rethinking a structure.’[2]

In the introduction of the same text, she firmly states, "A theorist is one who has been undone by theory. Rather than the accumulation of theoretical tools and materials, models of analysis, perspectives and positions, the work of theory is to unravel the very ground on which it stands. To introduce questions and uncertainties in those places where formerly there was some seeming consensus about what one did and how one went about it.”

Should a curator in analogy be one who is undone by art? (Temporarily) destabilized, overpowered, overwhelmed by the artworks that he or she encounters, by (contemporary) art in general which seems to be the perpetual unknown? One who at first is disarmed, then takes heart and not tries to vanquish but to tame the beast. Being a curator seems to be a lonely profession - or should we rather call it a state of being, a mode of operating, a way of giving sense and meaning? - as there are still very few set parameters and dominant paradigms to rely on or to rebel against.

It could be a question of balance .

A fictitious case-study or rather a case-study derived from fiction might shed some light on the matter at hand. Consider the "mad professor" Dr. Nathan in Ballard's novel The Atrocity Exhibition whose self-organised "show" in a forlorn cinema consists of the " corpses" of automobiles and a wide selection of photographic images of torture sessions, explicit violence and the after- effects of bombings and killings. Dr. Nathan's central engine in making this (imaginary) exhibition is "blind and deaf" obsession. He organizes this display in order to communicate this obsession to those "outside of his own mind" and to get an insight into the what and how of his compulsive interest in distorted bodies and the intrinsic eroticism of modernist architecture and crashed cars, the incessant and all-pervasive mediatized violence that surrounds him and excites him.

We could also consider a recent Prototype. The accomplished ‘curatorial student' who has obtained a postgraduate degree in Critical Studies or has completed one of the many Curatorial Programs that currently proliferate in the Western Hemisphere.The "generic" student characterizes him or herself by an excessive awareness of the ethics and unstable methodologies of curating, and can nevertheless not refrain from re-iterating the same curatorial questions ad infinitum without ever providing anything more personal than a series of bland, not to say clichéd, responses to questions such as "is the Biennale still a viable format", "in what does the author-curator differ from the artist-creator" and "how does the exhibition function both as a discursive format and as form of physical display”?

They - Ballard's Dr. Nathan and our Prototype - might as well be the sun and the moon. No gravitational force will ever bring those two proverbial “celestial bodies" in close proximity to each other although it seems that the key to "curatorial wisdom" is not to be found on either of those planets. It would seem that Dr. Nathan would have to unlearn obsession and that Graduate x would have to be able to abandon or at least transgress his or her hyper-awareness or compulsive meta-reflection and return to a moderate form of subjectivity. Anybody who aims at being more than a mere "logistics manager" in the curatorial field and equally wants to refrain from taking up the authorial/auteurial position, might consider undoing or unlearning a certain type of professionalism that prevents one from making intuitive decisions that are not based on well-founded arguments whilst simultaneously avoiding rash "gut-feeling"decisions that produce unreadable inconsistency and communicative failure. A useful instrument of navigation in this process could be “informed intuition" as American artist Sturtevant calls it. Using a clear-headed reliance on primal responses while making use of the theoretical tools and arguments that "education" has provided. Allow idiosyncrasy, avoid erratic randomness. I would like to call it being "moderate:" move between the twin poles of "structured knowledge" (that which is certain and acclaimed) and ultrapersonal impulses (the swamp of uncertainty).

Is there any way that this kind of moderateness - the middle way that for once does not mean or signify compromise - can be taught? Personally I have been educated in what we could call the “master-pupil" dynamic as eloquently described by George Steiner in Lessons of the masters.[3] Between master and pupil power and experience are unequally distributed: the mentor is "superior" and unilaterally instructs and"transfers" his or her knowledge to the “disciple" who absorbs whatever is transmitted and in a later stage might object to or intellectually and emotionally rebel against the received knowledge that he or she has been spoon-fed. Initial submission and subsequent opposition are the key concepts in this process as defined by Steiner. In his conservative and “romantic" view the inevitably charismatic - or charismythic -master a la Socrates and Jesus Christ has followers who receive his or her wisdom through a heady mixture of persuasion and seduction. Despite the fact that I value a more “lenient” notion of mentorship - as an ongoing charged personal encounter between one who "emits" and one who however reluctantly"receives" and which results in a remodelling of the "whole person" - I was, while restructuring the Curatorial Programme at de Appel in 2006, faced with the impossibility of reinventing and simultaneously institutionalizing mentorship without falling into the pitfalls of Steinerian thinking. In my view mentorship - and let's not think of Abelard and Eloise but of more productive and reciprocal relationships between the experienced and the uninitiated - basically relies on the adagium "Learn from the mistakes that others have previously made" and "whet the blade of your thinking on the stone of their experience’. Mentorship occurs randomly, by accident and by coincidence, it cannot be forced nor organised. What can be organised, however, is a situation in which one learns from each other's mistakes, whether these mistakes are made out of productive doubt or out of blind, stubborn conviction seems hardly relevant.

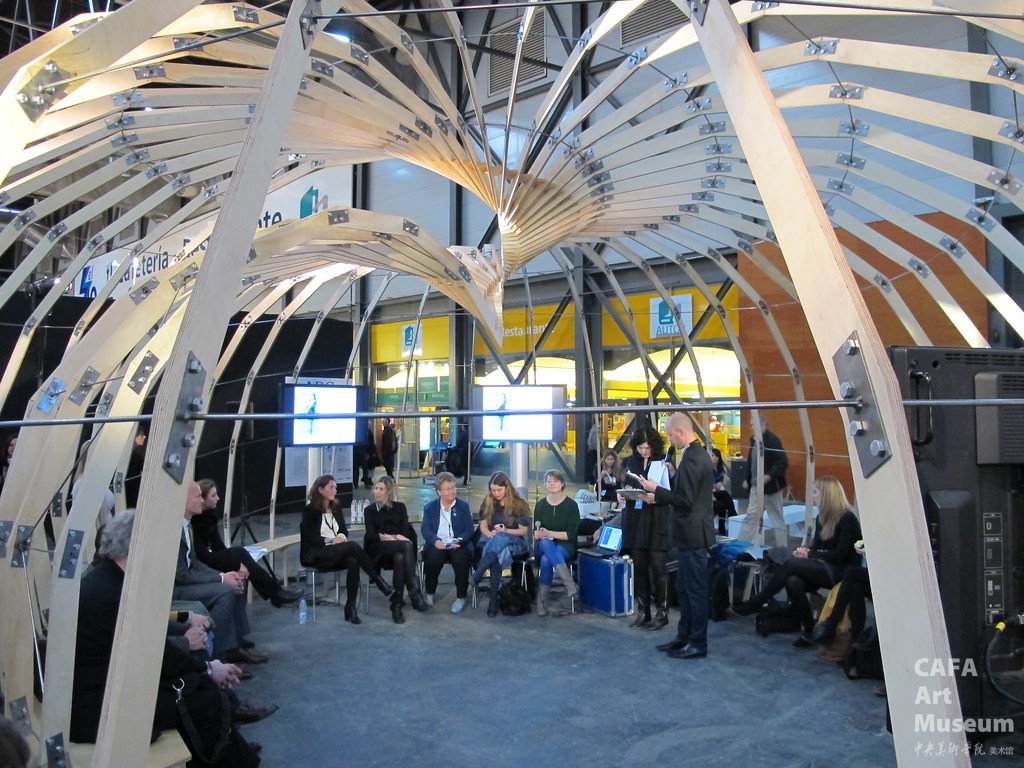

De Appel arts center, Amsterdam

In trying to move away from the inegalitarian form of Steinerian pedagogics, I inevitably had to reread Ranciere's The Ignorant Schoolmaster - Five Lessons in Intellectual Emancipation,[4] a book that curators of all kinds refer to continuously and repeatedly. In this publication, Ranciere advocates the methods of"universal teaching" as initiated by the I9th century French teacher Joseph Jacotot, who taught his Flemish pupils in Louvain - who were unable to speak French - to speak that language on the basis of an intense study of a bilingual edition of Fenelon's Telemaque (1699), although he was not able to understand nor produce the mother tongue of his young protégées. He relied on their natural intelligence and will power, and abstained from an authoritarian method of teaching. Ranciere formulates it as follows, "Jacotot had taught them something. And yet he had communicated nothing to them of his science. So it wasn't the master's science that the student learned. His mastery lay in the command that had enclosed the students in a closed circle from which they alone could break out. By leaving his intelligence out of the picture, he had allowed their intelligence to grapple with that of the book. Thus, the two functions that link the practice of the master explicator, that of the savant and that of the master had been dissociated.[5] It would be pretentious to claim that the de Appel Curatorial Programme was directly reformatted on Jacotot’s ideas - in an interpretation by Ranciere - but it can be said that the basic premise of Jacotot' s/Ranciere’s thinking on the subject has been taken as a point of departure. It aims to obliterate the "false" division between the so-called knowing, capable, and mature on the one hand and the ignorant, the incapable, and the unformed on the other hand. lt also assumes that knowledge transfer happens through story-telling and auto-education and not through explication, and that learning is a reciprocal process in which both"master" and "pupil" accumulate experience and new insights.

There is not only one way to surmount an obstacle, not only one way to rinse, refine, and polish an idea, opinion, or concept. As the field of art is moreover not one in which fact-checking comes easy and personal truths are favoured over convention, it often feels as if we are all blind men groping around in the dark room for a cat that is not there.[6]

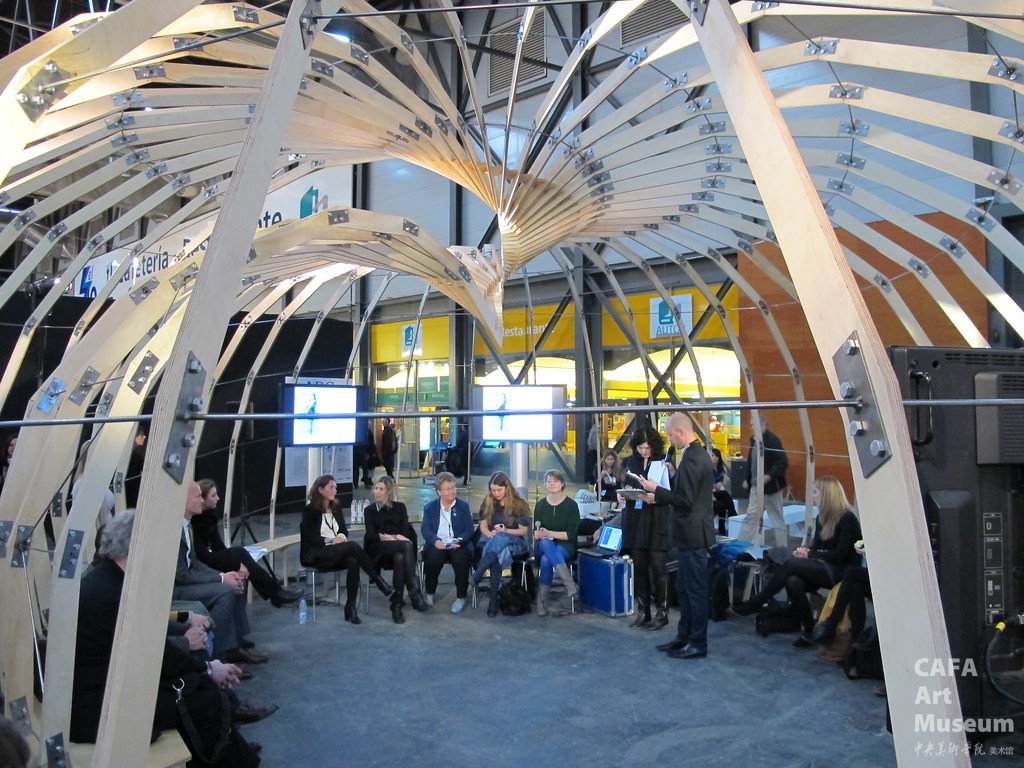

It seems the ultimate contestation of one of Pieter Brueghel's most well-known paintings "The Parable of the Blind" or "The Blind Leading the Blind.”[7] In the Pulitzer Prize-winning Pictures From Brueghel and Other Poems (1962), William Carlos Williams called the canvas "this horrible but superb painting, a laconic gloss on an equally laconic pictorial reading of Matthew 15:14 - 'Let [the Pharisees] alone: they be blind leaders of the blind. And if the blind lead the blind, both shall fall into the ditch.'"[8]

Pieter Brueghel, The Parable of the Blind

If we want to find our way in what is out of focus, blurred and shrouded in nebula, groping around and feeling our way through to the "knowing" and"learned ignorance" rather than knowledge, the blind might be the best guide to direct and lead the blind.

The original artical is published in "the Invisible Hand: Curating as Gesture", 2014

1 Translated from Michel de Montaigne, Essaies, Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Boom, p.369.

2 Katharyna Sykora, et al. (ed), "What is a Theorist?", Was Ist ein Kunstler?, Wilhelm Fink Verlag, Munich, 2004.

3 George Steiner, Lessons of the Master, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003.

4 Jacques Ranciere, The Ignorant Schoolmaster: Five Lessons in Intellectual Emancipation, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1991.

5 Jacques Ranciere, The Ignorant Schoolmaster: Five Lessons in Intellectual Emancipation, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1991, p.14.

6 Reference to the title of an upcoming group show at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, curated by Anthony Huberman.

7 Pieter Brueghel, "The Parable of the Blind" (1568). Oil on canvas, approximately 34 inches x 61 inches (86 x 154 cm). Museo e Gallerie Nazionali de Capodimonte, Naples.

8 ln "Eyeless with Brueghel,” Leigh Hafrey, The New York Times, January 26, 1986.