The exhibition “Leonardo and His Outstanding Circle”, which will open on September 12 at CAFA Art Museum, displays the inheritance of Leonardo da Vinci’s legacy with the example of the relations between the master and his circle. On September 11, curator Nicola Barbatelli held a lecture to introduce the exhibition’s background and works on display.

Mr. Barbetalli believes that it’s important to study Da Vinci’s circle, because it can help us understand better the techniques of Da Vinci’s group, through which we can further distinguish between the techniques he learnt from Verrochio and those he innovated and developed later by himself.

Before discussing Da Vinci’s circle, Mr. Barbetelli first introduced his early life, when he served his apprenticeship in Verrochio’s workshop. During this period, da Vinci created works such as Study of a Tuscan Landscape (1472), The Annunciation (1472-1475), and the Dreyfus Madonna (1475-1480), which revealed the artist’s outstanding talent. According to Barbetelli, Leonardo gradually excelled Verrochio in techniques, which ultimately led to him leaving the workshop.

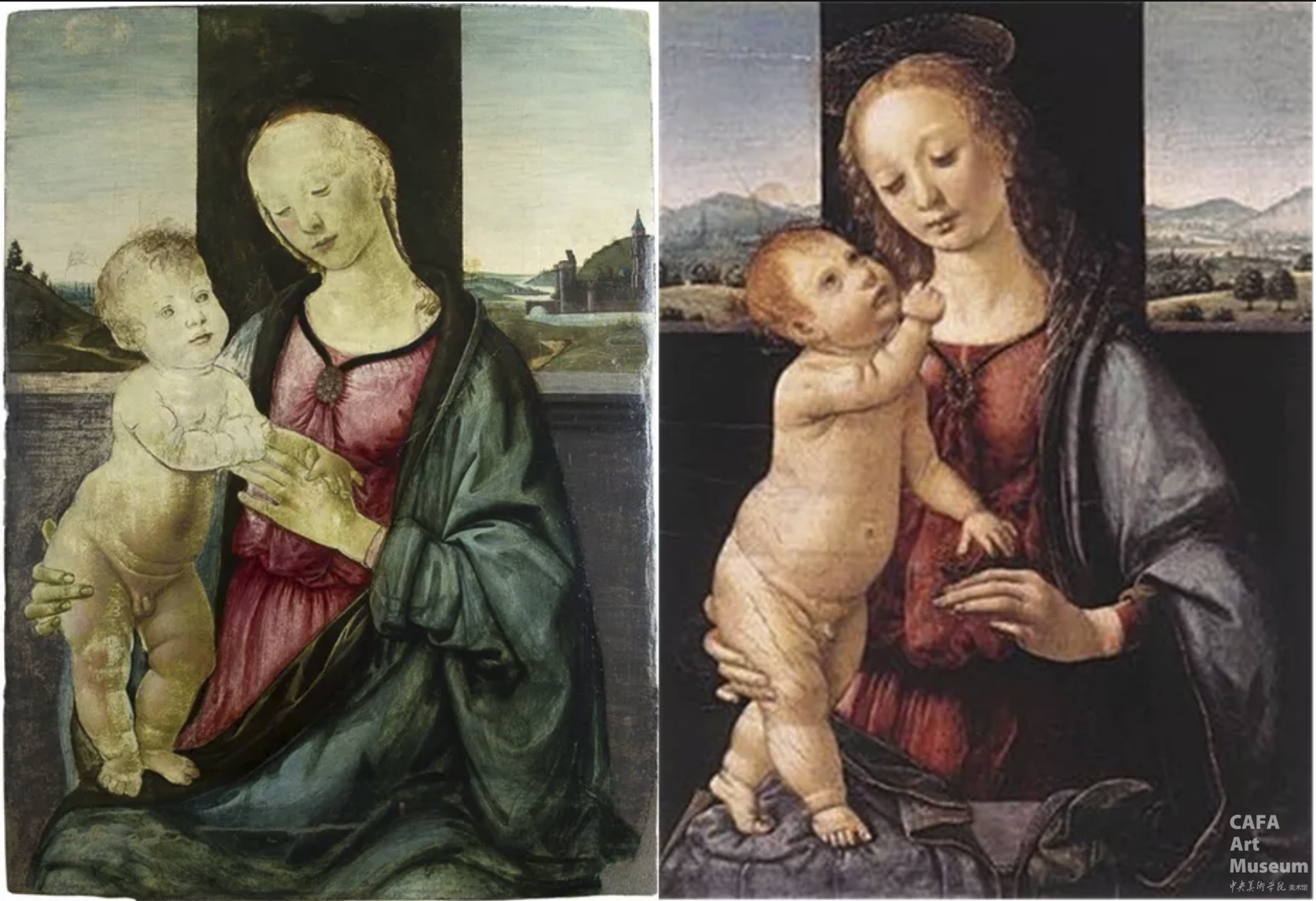

Dreyfus Madonna, Verrocchio (left) and Leonardo da Vinci (right)

Working on himself offered Leonardo more space to innovate and experiment, and to transcend the Florentine influence he received. For example, he continued his experimentation on the principles of perspective that could already be seen since The Annunciation, in which the Virgin’s right arm seems to be longer due to foreshortening.

The Annunciation, Leonardo da Vinci, circa 1475-1476, Uffizi Gallery of Florence, Italy

When Da Vinci arrived in Milan in 1480s, during his creation of Virgin of the Rocks, he collaborated with the brothers Ambrogio, who painted panels for the altarpiece. This is believed to be one of the first collaborations Da Vinci did. In 1490, he began to wrote about his followers in his diary, mentioned Salai, Giampietrino, Oggiono and Luini, and three other names. Da Vinci recorded not only the followers’ learning process, such as how they were asked to repetitively imitate Da Vinci after he roughly outlined a composition for them, but also their’ anecdotes, for example he described in detail how Salai, on the evening of September 7, 1490, broke a flask worth 22 silver coins at a dinner. It can be told from Da Vinci’s own record that he was very strict to the followers, forbidding them from using painting brushes or pigments, and requiring them to only use pencil. The goal was for them to catch a model’s likeness even without the model's existence. A style thus became more and more distinct in the group.

Virgin of the Rocks, Leonardo da Vinci, 1483-1486, Louvre, Paris

The style can be told from the collaborations between Da Vinci and his followers, such as two versions of The Madonna of the Yarnwinder, one of which is shown in this exhibition, Virgin of the Rocks, confirmed by scholars to be a collaboration with at least two other artists, and Bare-Breasted Magdalene, painted by Da Vinci and his assistant (while some scholars believe the assistant is Giampietrino, Barbetelli believes that it’s Oggiono).

Bare-Breasted Magdalene, Leonardo da Vinci and his follower (attr.)

What impresses the curator team is the followers’ capability to comprehend Da Vinci’s idea and style in religious paintings. However, Barbatelli said that it’s more challenging for them to capture the essence of Da Vinci’s portraits, as Da Vinci was revolutionary in his representation of the subject’s expression and posture. The followers had made several attempts to imitate Da Vinci’s portraits, but none of them reached the height of the original.

Three portraits by Da Vinci's followers

Da Vinci had to flee Milan at the end of the 15th century due to French army’s invasion. For Da Vinci and his followers, the downfall of Ludovico il Moro meant they lost their patron. Many of them went to Venice, set up their independent career and and spread the name of Da Vinci through their practice in northern Italy and Europe. The popularity of Da Vinci in Milan also sets a stage for these followers, who have grown mature under their master’s training.

By the time Da Vinci returned to Milan in 1506, his style had evolved after more researches. This can be told from both completed works and sketch drafts, although for the latter it can be better told from the comparison with the completed imitations by his followers. For example, while the original of Leda and the Swan was lost, we can retrieve some lost information from two copies by Giampietrino.

Leda and the Swan, Leonardo da Vinci (sketch on the left) and copies by Giampietrino (on the middle and right)

Due to Leonardo’s popularity at his time, many painters imitated his works. Barbatelli believes that his followers made great contributions in the inheritance of Da Vinci’s knowledge. For example, it was Da Vinci’s pupil Franceso Melzi who compiled his notes. After Da Vinci’s death, Luini and Giampietrino continued to operate their studios and accept commissions from the collectors who still desired for Da Vinci’s works. Their studios continued Da Vinci’s legacy till 1550-60s.

What Barbatelli believes to be the most important legacy of these followers’ works, or the works Da Vinci collaborated with them, is the humanist spirit and style characteristic of Da Vinci himself. From these works we could also learn about how Da Vinci educated people, conveyed his artistic spirit and passed on his legacies.

Time: 2019.9.11, 18:30

Venue: CAFAM Lecture Hall

Speaker: Nicola Barbatelli, curator of the "Leonardo and His Outstanding Circle" exhibition, director of the Museo delle Antiche Genti di Lucania

Presenter: Gao Gao, Director Assistant of CAFAM

Lecture photo(Credit: Li Biao)