Over the past 20 years, the role of art criticism has dramatically declined, as critics have been first stripped of a say by curators and then constantly challenged the theoretical bottom line by “rebellious” artists, with no shortage of warnings of “art criticism is dead!” [1] Under the double impact of commercial culture and ideology, the “seriousness” of art criticism is strongly questioned. It is easy for critics to turn into propagandists revolving around galleries and art museums to support their exhibitions and feeding the media with snackable contents.

For more than a century, art criticism has been regarded as a privileged form of writing with a conscience. Critics’ perceptive, insightful and passionate writings have played a key role in guiding both the artist and the public. In the Western art world, art criticism flourished after World War II, when the center of art shifted from Paris to New York. With the influence of Cold War, critics represented by Greenberg not only introduced American Abstract Expressionism to the world, but also developed a system of art criticism dominated by modern Formalism with their followers, which laid the theoretical groundwork for the later art criticism, curation and formalism, coined practical art terms for modern art theory, curation and media, such as plane, easel painting, visual space, and so on, and further defined the taste of modern art and distinguished modern galleries, art museums from traditional museums and art museums.

From the late 1960s to the 1970s, with the rise of left-wing sociology and neo-Marxism, modern formalism was gradually losing its appeal, and art criticism attached increasing importance to sociological interpretation. The theories developed by postmodern theorists from Paris, such as Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, Jean Baudrillard, Jean-François Lyotard, Jacques Lacan, Hélène Cixous and Luce Irigaray, have become academic concentrations – whether in the study of art history or in modern and contemporary art criticism, discussions of “deconstruction” and “archaeology” have emerged for analyzing the sociopolitical content in art, especially controversial issues of gender, class and race. The Marxist art historian T.J. Clark and those long-time art critics for The October Magazine, such as Rosalind Krauss, Hal Foster and Benjamin Buchloh, picked up the social issues Greenberg dismissed before, advocated the intervention of art into society, opposed the commercial system, and incorporated formal analysis into the historical narrative. [2]

At the peak of the feminist movement in the 1970s, female scholars in the United States played a significant role. Linda Nochlin was the first to pose the crucial question, “Why have there been no great women artists?” [3] She not only criticized the unequal art education in history but also revealed the prejudice existing in the writing of art history, in the selection of art institutions and even the entire cultural construction model. In order to change this reality, Nochlin personally participated and curated the exhibition Women Artists: 1550-1950, which made the neglected female artists leave a mark on art history. [4] This kind of criticism and curation combining with the study of art history had a direct effect on the operations of the entire American art organizations and the collection of art museums. Since then, many art exhibitions in the United States have significantly increased the proportion of participating female artists. The art historian Griselda Pollock integrated feminism with Marxist theory to further analyze the social-political reasons why women have been overlooked and marginalized. Lucy Lippard’s art critiques brought feminist issues from the edge of social thinking to its center. She supported women artists like Eva Hesse and Judy Chicago, and also defended many socially alienated artists. [5]

Since the late 1980s, art criticism has become more diverse. After the postmodernist theory deconstructed the core concepts of all art, the American philosopher Arthur Danto declared that by the advent of Pop Art, art had come to an end. Subsequently, art and art criticism have turned to philosophy. [6] Not only does Danto perceive art criticism as philosophy, but he also argues that “In a sense, the philosophy of art is actually art criticism.” [7] Taking Andy Warhol’s Brillo Boxes as an example, Danto’s art critique demonstrates the philosophical proposition “What Art is” and provides a rational basis for analyzing Pop Art and the following conceptual arts. [8]

Criticism as Interpretation – Danto’s Philosophy of Art

According to Danto, “whatever appreciation may come to, it must in some sense be a function of interpretation.” [9] He explains that the function of criticism is to identify and interpret artworks presented in different ways and to engage in defining art theory through reasoning and discussing, so as to elucidate how art becomes art and what kind of meaning it contains. [10]

Danto’s practice of art criticism interprets art images with philosophy, which transcends the aesthetical level of a pure evaluation of taste and enters into ideology and culture. As a critic for The Nation, Danto once commented that Jeff Koons’s works looked as if they had just been picked up from a thruway gift shop, and they amplified the “vulgarity” of everyday life, no less than “a vision of an aesthetic hell”. [11] The work Pink Panther (1988) looks like a homely knickknack but is almost life-size. Jeff Koons drew on the fairy tale story “Beauty and the Beast” yet deviated it from the original work’s idea of innocence. Flashy appearance and sexually provocative postures render more satire than Andy Warhol’s Golden Marilyn Monroe.

Jeff Koons, Pink Panther, 1988, porcelain sculpture

However, Danto does not negate the significance of Koons’s works. Back to the philosophical question “What Art is?”, Danto points out that as a new-generation representative of Pop Art, Koons’s works, following Warhol’s, struck a more fatal blow to the taste of art, presenting the commercial culture of late capitalism. Danto also notes that viewers were less inclined to be put off when they saw Koons’s works installed in the vast space of Whitney Biennial, because it was more like one of the elements for making up a big patchwork of diverse contemporary arts. While being placed in the confined space of the gallery, Jeff Koons’s works took up the whole space as if taking over the world, very suffocating. [12]

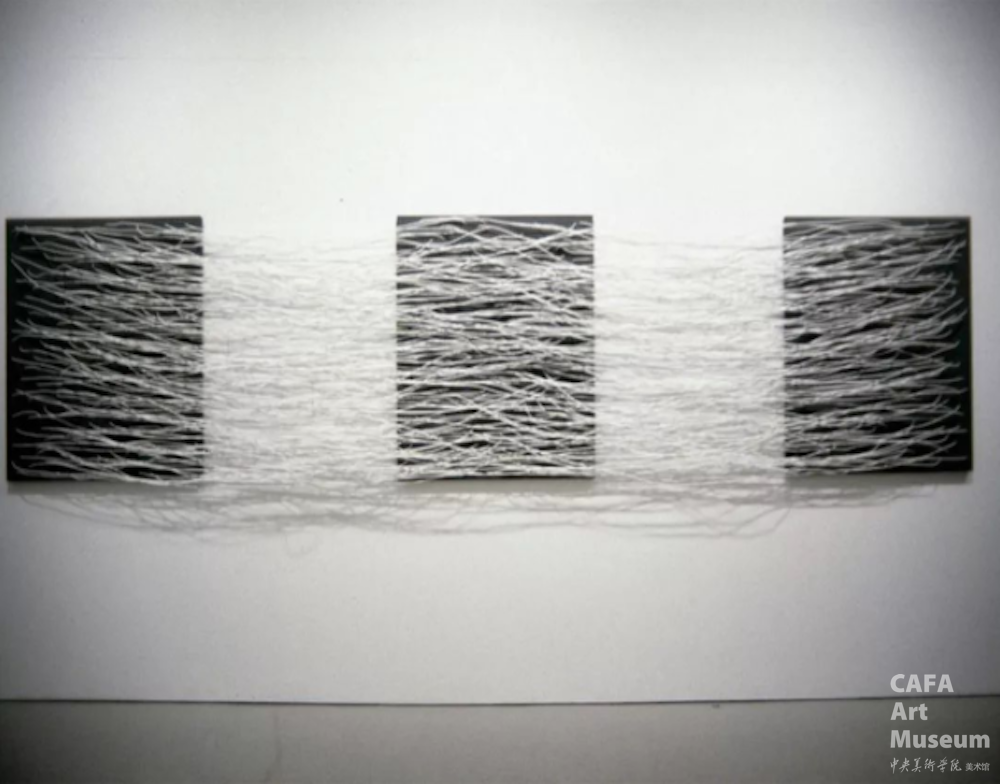

Danto also defended the female artist Eva Hesse against critic Hilton Kramer’s argument of referring to Hesse’s sculptures as a transformation of Pollock’s abstract expressionist painting. Because abstract expressionism is not the only quality that can be found in Hesse’s works, and instead, she is more closely associated with minimalism and structuralism. [13] Hesse’s Metronomic Irregularity II was featured in the “Eccentric Abstraction” exhibitions organized by Lucy Lippard, who was originally disappointed with Hesse’s selection of this work for the show due to its apparent lack of sexual and organic qualities. Hesse was interested in something relatively free of erotic overtones. Her brilliant performance lies in piecing together minimalist forms and abstract expressionism. The equal-sized black pieces of slate with spaces of blank walls between them speak of the beauty of the minimal form, synthesizing the color-field of abstract expressionism and the visually muted minimalism. The interaction of these different sources of inspirations creates a dissonance that gives the work a unique intensity, reminiscent of the beat of a clock and the disarray of a storm, thus reflecting harmony in disharmony.

Eva Hesse, Metronomic Irregularity II, 1966, painted wood, sculp-metal and cotton-covered wire, which is no longer in existence

In the case of interpretative art criticism, it is likely to “turn a brick into gold”, which thus especially relies on whether a critic has artistic accomplishment or not. Danto’s way is to include aesthetic evaluation in art criticism besides interpreting the meaning of works of art. In reviewing David Hockney, for example, Danto analyzes that his works went through a period that was artistically less expressive, but he recovered in 1977 with his painting My Parents, distinguished by his outstanding performance in dealing with perspective, details, and emotions, considered as one “among the masterpieces of the century”. [14] Hockney made this painting a year before his father’s death, with a great emphasis on detail, in which the portrait of his mother looks quiet and elegant, while his father, who seems a bit unsettled, is shown reading Aaron Scharf’s Art and Photography. On the cabinet shelf is a picture book on Chardin, the 18th-century French realist painter and several volumes of the stream-of-consciousness novel Remembrance of Things Past by Marcel Proust, an early 20th-century French writer, echoing with the intimate scene of domestic life. The reflection of Piero della Francesca’s The Baptism of Christ in the mirror forms a triptych with the two figures in the foreground, evoking the passage of time and the solemnness in banality.

David Hockney, My Parents, 1977, oil on canvas, 182.9 x 182.9cm, Tate

In the way of looking at works of art, art criticism has always had a philosophical meaning in essence. As an interpreter of art, Danto’s art criticism explores many profound matters, such as the nature of love, the meaning of life, the relationship between society and man, and so on. However, art is fundamentally about art, and it is different from the object of study in philosophy, otherwise, it would be an illustration of philosophy. Danto himself believes that although art has come to an end, philosophy would not transcend art. In his view, philosophy is simply hopeless in dealing with human issues, while art has more depth and profundity and can tackle a wide range of issues. In The Abuse of Beauty, he even said, “When I think of Jan van Eyck’s portrait of the Arnolfini couple against what philosophers have said on the topic of marriage, I am almost ashamed of my discipline.” [15]

Indeed, painting can be used to record a scene at the moment, and also describe a situation that words just can’t explain. In 1934, when Jan van Eyck made the portrait of the Arnolfini couple, in addition to the depiction of the couple, he also paid attention to the expression of the social custom, moral orientation and delicate emotions at that time. In the picture, Arnolfini, who was a merchant from Lucca but resident in Bruges, is raising his right hand at his house as if greeting the audience. His wife has a swollen belly, but not pregnant, because she is dressed in a prevailing extensive skirt. The painter exquisitely depicted the interior furnishings and the puppy to symbolize the fidelity and stability of marriage and the affluence of life. The convex mirror in the middle reflects two figures standing in the doorway, one of whom is the painter himself. Inscribed on the wall above the mirror is the artist’s name, both a signature of the painting and a witness to the moment: "Johannes de eyck fuit hic 1434" ("Jan van Eyck was here 1434"). The artist made full use of the texture of oil painting to render the picture a fine and subtle lighting effect – particularly shown on the glittering brass chandelier. With the medium of oil painting, Jan van Eyck conveyed a sense of beauty, value, history and presence that goes far beyond what can be written down or described by language.

Jan van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434, 82.2cm x 60cm, egg tempera and oil on wood, The National Gallery in London

Art Criticism as Evaluation– Elkins’s View on Criticism

In the book What happened to art criticism? [16] by James Elkins, he presents a wealth of evidence suggesting that art criticism today has no one to show any interest in as it is neither attractive nor academic. It is not much read by ordinary people, nor is it used in research by art historians. Especially those art critical writings serving the purpose of promotion for galleries and artists are equivalent to factory products or chef’s dishes that must cater to the tastes of buyers.

According to Elkins, art criticism is divided into seven types, including the catalog essay, the academic treatise, cultural criticism, the conservation harangue, the philosopher’s essay, descriptive art criticism, and “poetic” art criticism.

1. The catalog essay: commissioned by galleries and art museums, it is the most popular type of art criticism today but is also the least read since they mostly end up as a pastime on the tea table.

2. The academic treatise: it sounds plausible but usually refers to reviews written by scholars for a painter or exhibition, often a collage of meaningless words and theories dedicated to overrating works of art. Such critical writings are not taken seriously by real academic art historians and less worthwhile for citation.

3. The cultural critic: some cultural scholars put art into a social context and relate it to current popular TV dramas and social issues, which they only talk about in general, unprofessional terms and cannot get to the point.

4. The conservative harangue: some critics deliberately make things difficult for transformative contemporary art with moral and aesthetic criteria.

5. The philosopher’s essay: Thomas Crow and Danto can be listed as representative figures. Elkins considers it hard to regard Danto as a critic due to the lack of a value evaluation system and historical coherence in his writings about art. When Danto declares that we have reached the end of art, he has not theorized the different new forces, which made his art criticism non-historical and difficult to be systematized and theorized.

6. Descriptive art criticism: most American art critics list this kind of writing as their primary purpose, which usually appears in newspapers and magazines, similar to the review of food or wine, without a reliable basis or quality guarantee, or even not clear which artist or works are worth writing about.

7. Poetic art criticism: critics of this sort use art as a platform for personal expressions, like Peter Schjeldahl, the leading critic of the New Yorker, and Dave Hickey who has a lot of art fans. They emphasize the expressive power of art, write well and persuasively, dare to speak the voice of the public, yet this is not enough to be seriously considered as the whole story about art criticism.

After examining these various categories of art criticism, Elkins proposes his own criteria of evaluation about art: first, an ambitious judgment; second, a reflection on this judgment; third, a criticism as important as art history, or vice versa. Although Elkins’s conclusion applies to American art criticism, it still has a good reference for global art criticism and the current status of Chinese art criticism, which is very important for the establishment of an art-historical, rational and evaluative criticism.

Art Escaping Criticism

In the 21st century, with the advent of the age of globalization, social, economic and technological changes have taken place in an unimaginable way, and art criticism is no longer affiliated to a trend or fashion, nor is there any model of criticism taking the lead. David Hickey, a critic retired from the art world, calls for the return of beauty; [17] while the art historian Donald Kuspit advocates a psychoanalysis-led art criticism. Influenced by the philosopher Ernst Cassirer, he believes that all forms are intrinsically expressive and symbolic, emphasizing the emotional depth of art and subjective expression of artists. [18] On the contrary, the art theorist Douglas Davis puts technology before aesthetics and stresses more the great influence of high technology on modern art. [19] After the intervention of social criticism in the post-modern period, formalist art criticism has risen again. After all, art has other functions apart from expressing ideas, such as imitation, appreciation and psychological therapy. Even in contemporary art, those old-fashioned words such as beauty, imagination and creativity, should not be replaced by social-political terms like “catalyst” or “mediator”, because art has always had a power of sensibility that is hard to be imagined in rigid theories.

Perhaps, art never needs criticism? Have artists always been breaking free from the shackles of art criticism? As early as the late 19th century, when modern art criticism was emerging, a Spanish artist Pere Borrell del Caso (1835-1910) used Trompe-l’oeil technique to depict the artist’s desire for free expression. In the oil painting Escaping Criticism, a little boy is seemingly climbing out of the painting, with his hands clinging on the frame, a foot already stepping out, his eyes wide in wonder with his first glimpse of the outside world as if a prisoner trying to escape from the cell. The artist seemed to criticize the phenomenon that theory has deprived art of its vitality. In the final analysis, the existence of art depends on the freedom of expression and breaking rules.

Spanish artist Pere Borrell del Caso, Escaping Criticism, oil on canvas, 1874

Why don’t art critics want to escape from constraints? The theory of art itself is original and meaningful. Oscar Wilde once said in his essay The Critic as Artist (1891) that art-criticism creation is the highest art. [20] Critics also hope to break the shackles from the art market, art organizations and institutions, to engage extensively in creative criticism, to reveal different aesthetic, social and political implications contained in art, not just confined to form or artists’ creation intentions.

Under the trends of cross-culture and cross-discipline, art criticism can be combined with a variety of disciplines to form a grand, omnidirectional and multidimensional system of criticism, and is also possible to have an unexpected encounter with different kinds of art theories, including the ancient Chinese art criticism system, so as to establish a dialogue between formal, psychological, moral, social and cultural factors. The boundaries of art history, philosophical theory, art planning and art criticism have been constantly crossed, where art historians can use a sharp perspective of criticism to get into historical research, and critics can also include the knowledge and profundity of art history and philosophy into criticism. Art criticism and art, only when they ceaselessly escape from constraints and pursue independent academic freedom, can they jointly create more far-reaching significance.

By Shao Yiyang

The original article is published in Art Research, No. 4, 2019

Reference

1 Please refer to Shao Yiyang, Beyond Postmodern, Peking University Press, 2012, pp. 114 -124.

2 Buchloh is an active art critic in recent years. His academic masterpiece is Benjamin Buchloh, Neo-Avant garde and Culture Industry: Essays on European and American Art from 1955 to 1975, MIT Press. 2003.

Please refer to the Chinese translation, Benjamin Buchloh, translated by He Weihua, Shi Yanlin and Qian Jifang, Neo-Avant garde and Culture Industry: Essays on European and American Art from 1955 to 1975, Jiangsu Phoenix Art Publishing House, 2014.

3 This article is first published on the cover of Art News, 1971. Please refer to Nochlin, L. “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” Art and Sexual Politics, Collier Books, 1973, pp. 1–39.

4 In 1976, Linda Nochlin and Anne Sutherland Harris co-curated the exhibition, Women Artists: 1550–1950 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and jointly wrote the preface of the exhibition catalogue.

5 Lippard defends artist Eva Hesse, which can refer to Shao Yiyang, After Postmodern, Shanghai People's Fine Arts Publishing House, 2008, pp. 73-75

6 Arthur Danto, "The End of Art", in the Philosophical Disenfranchisements of Arts, New York, 1986, 81-115.

7 Arthur C. Danto, The State of the Art, Prentice-Hall, New York: 1987, 3.

8 Please refer to Arthur C. Danto, The Transfiguration of the Commonplace: A Philosophy of Art, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1981. Please refer to the Chinese translation, Arthur C. Danto, translated by Chen Anying, The Transfiguration of the Commonplace: A Philosophy of Art, Jiangsu People's Publishing House, 2012.

9 Arthur C. Danto, The Transfiguration of the Commonplace: A Philosophy of Art, Harvard University Press, 1981, 113.

10 Arthur C. Danto, "The Art World Revisited," in Beyond the Brillo Box: The Visual Arts in Post-Historical Perspective, University of California Press, 1992,41.

11 Arthur C. Danto, Encounters and Reflections: Art in the Historical Present, Farrar Straus Giroux, New York, 1990, 280-281.

12 Ibid.

13 Arthur C. Danto, Encounters and Reflections: Art in the Historical Present, Farrar Straus Giroux, New York, 1990, 197.

14 Arthur C. Danto, Encounters and Reflections: Art in the Historical Present, Farrar Straus Giroux, New York, 1990, 200.

15 Arthur C. Danto, The Abuse of Beauty: Aesthetics and the Concept of Art Open Court, Chicago and LaSalle, 2003, 139.

16 James Elkins, Whatever Happened to Art Criticism?, Prickly Paradigm Press, Chicago,2003.

17 Dave Hickey, The Invisible Dragon: Essays on Beauty, Revised and Expanded, University of Chicago Press, 2019. Please refer to the Chinese translation, Dave Hickey, translated by Zhuge Yi, The Invisible Dragon: Essays on Beauty, Revised and Expanded, 2009, Jiangsu Phoenix Art Publishing House, 2018.

For Hickey and Danto’s debate on beauty, please refer to Shao Yiyang, Global Perspective in Contemporary Art, Peking University Press, 2018, 213-216.

18 Donald Kuspit, Redeeming Art: Critical Reveries, Allworth Press, 2000.

19 Douglas Davis, Art and the Future: A History Prophecy of the Collaboration between Science, Technology and Art, Praeger Publishers, New York, 1973.

20 Josephine M. Guy, ed., The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, vol. iv, Oxford University Press, 2007.